Your Pulmonary Fibrosis Questions Answered

Our readers have submitted some great questions. We value your questions and encourage you to continue to tell us about your interests and questions.

What can be expected when a patient develops abrupt respiratory failure on a background of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis?

IPF is an unpredictable disease. There can be long periods of months to years of relative stability. Gradual decline may occur, as can abrupt periods of deterioration. These periods of rapid decline are characterized by increased shortness of breath, worsening oxygenation and often increased cough that develop over a period of a few days to a couple of weeks.

IPF is an unpredictable disease. There can be long periods of months to years of relative stability. Gradual decline may occur, as can abrupt periods of deterioration. These periods of rapid decline are characterized by increased shortness of breath, worsening oxygenation and often increased cough that develop over a period of a few days to a couple of weeks.

There are a limited number of reasons that a patient with IPF may decline rapidly. We consider the possibility of pneumonia, heart failure, blood clots in the lungs and abrupt acceleration or exacerbation of the underlying IPF. We often have to treat for multiple possibilities while we are trying to identify a cause of the decline. If we don’t see evidence of heart failure, pneumonia or blood clots, then we make the diagnosis of an IPF exacerbation.

Treatment for IPF exacerbations is not great. We generally use high dose steroids and provide supportive oxygen. Some patients recover but others do not and end up progressing and dying from respiratory failure. Patients that require mechanical ventilation (support of a breathing tube and breathing machine) are at greatest risk for death. Patients that have an identified cause for their decline such as pneumonia or heart failure tend to do better but the outcomes are always very guarded.

Can NSIP (Non-Specific Interstitial Pneumonia) transform into IPF?

NSIP is a type of interstitial lung disease characterized by ground glass opacities and some scarring on CT scan. On lung biopsy there is a more uniform distribution of inflammation within the lung and generally less scarring than IPF.

There are two broad types of NSIP, cellular and fibrotic. Cellular NSIP generally responds well to treatment with steroids and other immunosuppressants. In contrast, fibrotic NSIP behaves somewhere in between NSIP and IPF. It does not respond as well to treatment with steroids or other immunosuppressants. When advanced, fibrotic NSIP can look very much like IPF. One of the major reasons to perform a lung biopsy in the evaluation of possible IPF is to separate NSIP from IPF.

We do not believe that NSIP can become IPF though they can both result in advanced scarring in the lungs.

Is there an optimal diet for patients with IPF?

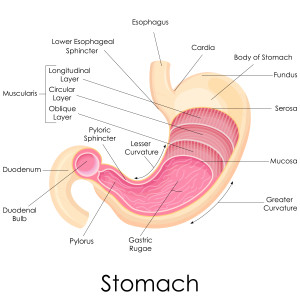

At present we don’t have compelling data that one type of diet is optimal for patients with IPF. However, some general points are applicable. Gastro-esophageal reflux is an important concern in IPF patients. As a result, we encourage our patients to limit their caffeine, alcohol, deep-fried and fatty foods. Dinner should be a smaller meal and lunch can be a bigger meal. Avoid snacks before bedtime. Many patients do better with the head of their bed elevated about 10 inches.

At present we don’t have compelling data that one type of diet is optimal for patients with IPF. However, some general points are applicable. Gastro-esophageal reflux is an important concern in IPF patients. As a result, we encourage our patients to limit their caffeine, alcohol, deep-fried and fatty foods. Dinner should be a smaller meal and lunch can be a bigger meal. Avoid snacks before bedtime. Many patients do better with the head of their bed elevated about 10 inches.

As IPF progresses, many patients begin to lose weight. This is probably caused by decreased intake and increased inefficiency of breathing. When this develops, changing the diet to avoid foods that require more work is helpful. For example, foods that require a great deal of chewing are more difficult. In contrast, softer foods, smoothies or liquid supplements are much easier to consume. Esbriet and OFEV are best taken with food to minimize side effects. You do not have to have a huge meal, but a yogurt, or piece of toast is adequate.